An end-of-year post I read last week cited the old Lenin quote: ‘There are whole decades when nothing happens and weeks when decades happen.’

Apparently Lenin never actually said that – though it might’ve plausibly been applied to an eventful period like the 1917 October revolution, also known as the ‘ten days that shook the world.’

By those standards, I’d posit that 2024 – while a truly exhausting year – was distinctly lacking in revolutionary events. We lived through frantic news cycles, feverishly observed, that pretty much failed to change the status quo.

In the summer, we saw assassination attempts that might have upset the course of history, but did not. At year’s end, a successful assassination on the streets of New York revealed a wellspring of anger without any outlet to generate structural change beyond hand-wringing think-pieces and thirsty memes.

Most anticlimactically of all, we had the unprecedented withdrawal of a US Presidential candidate, but after such a long delay that the dreaded outcome it was meant to avert came about anyway.

The mood of the year was such that even the fall of Assad’s murderous regime in Syria, after twelve years of civil war, prompted little sense of hope or renewal. Somehow, we suspected, this turning point would slot into the 2024 pattern of regressions, setbacks, stalemates and ongoing atrocities that show little likelihood of ceasing.

Whether Lenin said it or not, some years do age you more than others.

This year, my forty-fifth, was notable for the urgency with which my body made itself felt. It was the year I learned a new vocabulary word, fascia, as in ‘living a sedentary lifestyle can shorten or stiffen fascia.’ Fascia are the thin fibrous tissue around your muscles and, in my case, if I don’t do some pretty dedicated stretching as soon as I get out of bed, activities I once took for granted – like sitting – can become pretty painful.

Like me, some democratic institutions we once took for granted have shown major signs of aging. From Europe to the United States, one senses a societal impulse to stiffen and shut down, to harden borders and police identities.

A large and powerful proportion of the population desires things to remain fixed in place, whatever the painful cost.

Subscribers may have noticed that, despite all that sedentary time at my laptop this year, I produced hardly any essays here. That’s partially down to a set of new theatre-writing projects that consumed more of my energy (about which I’ll say more another time) but also to a suspicion that my essayistic insights were hardly appropriate to the gravity of world events.

As the months of 2024 wore on, the half-completed drafts of half-baked theses accrued. No one will ever learn the links I semi-perceived between heroic but untrusted sleuth Jaz of The Traitors UK-fame and gamesmanship in Middle East Diplomacy. That’s probably for the best.

Someday I hope to complete my long-gestating tribute to stalwart radio host Terry Gross of NPR’s Fresh Air and her decades-long imprint on my consciousness. The moment seemed particularly ripe this summer, if only because Terry presented such a striking counterpoint to the angst surrounding Biden’s waning abilities and refusal to anoint a successor:

Knowing that Fresh Air is a forty-year old media brand almost entirely wrapped up in one aging woman’s personality, Terry and her Fresh Air staff have worked with typical patience and sagaciousness to ease listeners into a new regime by quietly announcing Tonya Mosley as co-host and allowing us to grow used to her interview style. Terry’s not gone yet, but the plan for succession is clear.

Elsewhere, though, 2024 was haunted by the failure to willingly and graciously transfer power: Trump’s criminal efforts to negate the election on Jan. 6th were the clearest of his many signs of unfitness for office, and yet Biden’s hubristic vanity prevented him from ceding his own power until it was too late. In France, the Left coalition helped Macron’s party hold back the far right tide and he still wouldn’t yield any Parliamentary power to them, with disastrous results. Netanyahu’s refusal to negotiate a ceasefire in Gaza stems in large part from his personal drive to cling to power and avoid criminal prosecution.

Our stiffened systems support a stagnant gerontocracy and seem to make the barriers for change increasingly insurmountable. Across the globe, ascendant political movements are backward-looking, invoking the supposed golden times before inflation, before widespread migration, before reproductive rights or gender-affirming care, as they roll back progressive policies.

In this context, perhaps it’s not really surprising that a film like Conclave should have struck a nerve in the 2024 prestige cinema lineup. After all, no system is as famously stiff as the Roman Catholic Church.

If you haven’t seen it, this hammy, old-fashioned melodrama curiously shares many of the trappings of a reality competition show. Think of it as Drag Race: Vatican City.

Dressed in full Ecclesiastical Eleganza, a collection of cardinals are vying to be crowned the next RuPope. The action is structured around a series of votes in which they deliberate over their ballots with the grandiosity of All Stars queens choosing which lipstick to select. Each of the leading contenders gets eliminated one by one, with secret alliances, confessionals, reveals and backstage interference along the way. Isabella Rossellini = Michelle Visage.

The makers of Conclave surely understood that this film about choosing a new leader would be viewed through the prism of the 2024 Presidential election. We have a coterie of ineffective ‘liberal’ bishops who can’t get their act together, leaving an opening for fascism in the form of a rabid traditionalist Italian Archbishop who longs to bring back Latin Liturgy and European supremacy. At one point, Stanley Tucci channels the opinions of citizens worldwide when he opines ‘Is this what we’re reduced to? To vote for the worst best option?’

This political allegory climaxes in a set of speeches that come just before the final, fateful ballot. The above-mentioned Italian argues for a full-on religious war against Muslims, with all the bile of Trump/LePen/Tommy Robinson: ‘We house them in our homelands, while they exterminate us!’ It falls upon a mysterious — and heretofore mostly silent — character, Cardinal Benitez, to offer a countervailing vision, delivered (and lit) in a manner that evokes the humble simplicity of Jesus himself:

‘The Church is not tradition. The Church is not the past. The Church is what we do next.’

Many a mystic or peace activist has drawn on this same unworldly logic to challenge the accepted order of things: War Is Over (If You Want It). A ceasefire begins once both sides cease firing.

The act is possible, if we only had the will.

[I am about the discuss the film’s shocker of an ending, which I’ll be coy about. But if you want absolutely zero spoilers, please skip the next paragraph…]

Benitez is at the center of the film’s final twist, which for some critics ruins the movie purely on a plot level; conservative commentators have denounced it as a ‘left-wing fever dream.’ Suffice it to say that the cardinal crowned Pope harbors a secret that is altogether different from those that scuppered the earlier candidates. It is an aspect of identity that lies at the heart of our culture wars. This patriarchal system has anointed someone with an understanding of gender that is not so rigidly locked in a binary system. Lord knows what J K Rowling would make of it.

[OK, no more spoilers! Feel free to read on safely…]

In the film’s concluding shot, Ralph Fiennes looks across a courtyard to see some young nuns, no longer sequestered, scampering out of the conclave’s stuffy confines. To dyed-in-the-wool Catholic lefties like myself, the image recalls the old anecdote about the reformist pope John XXIII telling the Second Vatican Council, ‘I want to throw open the windows of the Church, so that we can see out and the people can see in.’

That symbolism feels too pat, especially in the face of a resurgent rightwing forces around the world. In a film that frequently strains credulity, the most soap-operatic touch is the notion that a stagnant and outdated system will miraculously produce a savior who represents its own undoing.

Restrictions on women’s reproductive freedom and gender-affirming care for trans youth will not be magically restored by the tip a papal fairy-godmother’s mitre. To those who must face such cold, hard facts, the windows appear firmly shut…

The longing for messianic deliverance manifests not only in fiction, however.

To many, the December arrival of Luigi Mangione delivered an end-of-year plot twist as unexpected and compelling as the conclusion of Conclave.

The fascination he’s inspired can’t be attributed entirely to his Instagram (or OnlyFans?) -ready hotness. After a year of setbacks, Luigi became a story that (some on) the progressive Left could chalk up as a ‘win’. He immediately became a figure upon whom to project a longed-for sense of agency in the face of vast, depersonalising systems — even if an objective examination reveals the tragedy of a young man driven by rage to take up a firearm, who will likely spend the rest of his life in prison.

Earlier this year, though, with less fanfare, other young people disregarded the law and took action against a depersonalizing health care system. Unlike Luigi, they haven’t shown us their faces; some of them are still minors and they prefer to act as an anonymous collective.

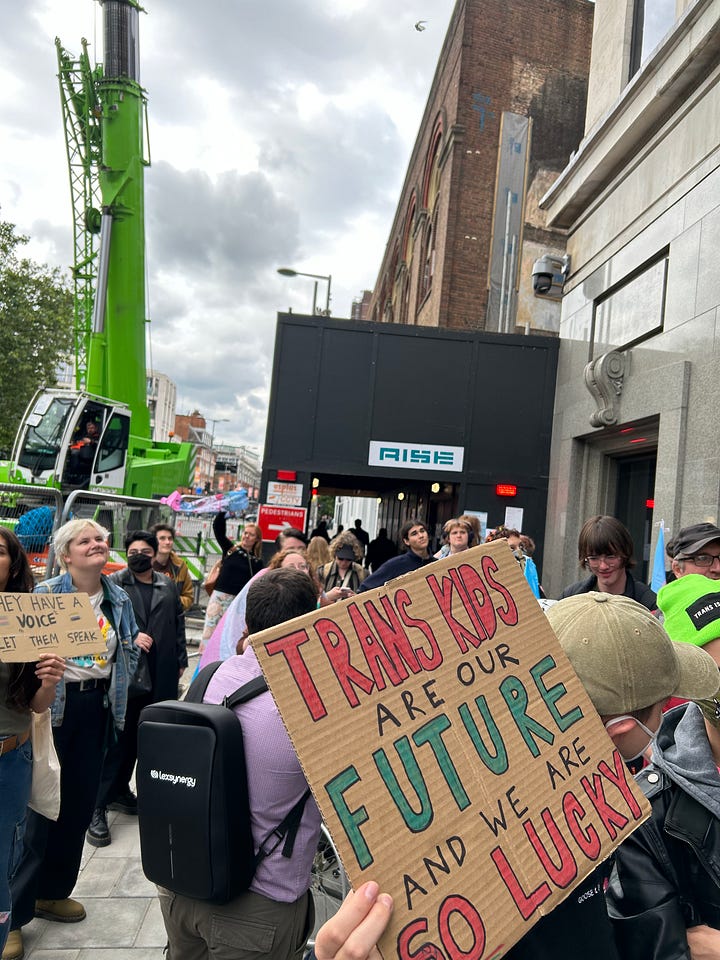

I first got wind of Trans Kids Deserve Better, the week after this year’s London Pride. Carrying the message ‘We Are Not Pawns for Your Politics,’ this collection of teens were occupying the window ledge of an NHS headquarters on Waterloo Road to demand access to life-saving gender-affirming care.

Their statement of purpose read in part:

We deserve to be heard in all matters which affect our lives. We’re not spectacles, we’re not objects, we’re people, and our lives are at stake.

When I saw the news on social media, with a request for allies to come down and show support, I didn’t need to look up where the building was. About ten years ago, I’d organised a protest at the very same spot, timed to coincide with a group of NHS bigwigs debating access to HIV prevention medication. This was the first effort in a long — and ultimately successful — campaign by many activists more dedicated than me to achieve free access to PrEP for anyone in England.

As I walked down the road toward the Trans Kids action, I did feel old – but not in the same way I do when my hips ache from a lack of proper stretching. Had it really been a decade since we’d started to wage that battle for proper HIV care? I felt very aware of the fullness of time, along with a sense of pride and gratitude for rights that younger people could now depend on.

On the pavement outside Wellington House were older queer activists, alongside straight allies, there to support these youngsters’ cause but also to make sure they were safe. In this situation, anyone over twenty-five counted as an elder. They were offering guidance to the next generation about how to handle the media and the police. They were there with food and water and holding the ladder to make sure that the Kids got down from the ledge without injury.

What the elders did not do was make speeches: they passed over the microphone and let the young people speak for themselves.

That’s when I started to cry. Not out of despair, but pride.

I’d spent that July day doing archival research into the actions of the 1984 Defend Gay’s the Word campaigners, who’d fought back against censorship and seizure of gay literature. That historic moment was a big and satisfying win, which more people ought to know about (which is why I’m part of a team turning that story into a musical), but it wasn’t a final victory. A few years after the case against Gay’s the Word was dismissed, gay-affirming books were part of the justification for Thatcher’s Section 28 policies, which lasted til 2003 and forbid the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality in education. Even today, more than half of school librarians in the UK have been asked to remove gay and trans books from their shelves.

These fights that we have to wage against depersonalizing systems are cyclical. The same themes and opponents keep recurring in new guises.

But when I looked up at that building, I saw a powerful lineage, a chain within which I was just one link. In 2014, my cohort of HIV activists had been inspired and tutored by the first generation of ACT-UP agitators who’d developed radical civil disobedience practices in the face of mass death.

Here the torch of that resistance was being taken up and transformed by our younger siblings, who were also fighting for their lives.

Just this past month, the Labour government announced an indefinite, harmful and unjustified ban on puberty-blockers for trans youth (though cis teens can still access the very same medications), brought in by the cowardly, openly gay Health Secretary Wes Streeting, who is a shame on the LGBT community.

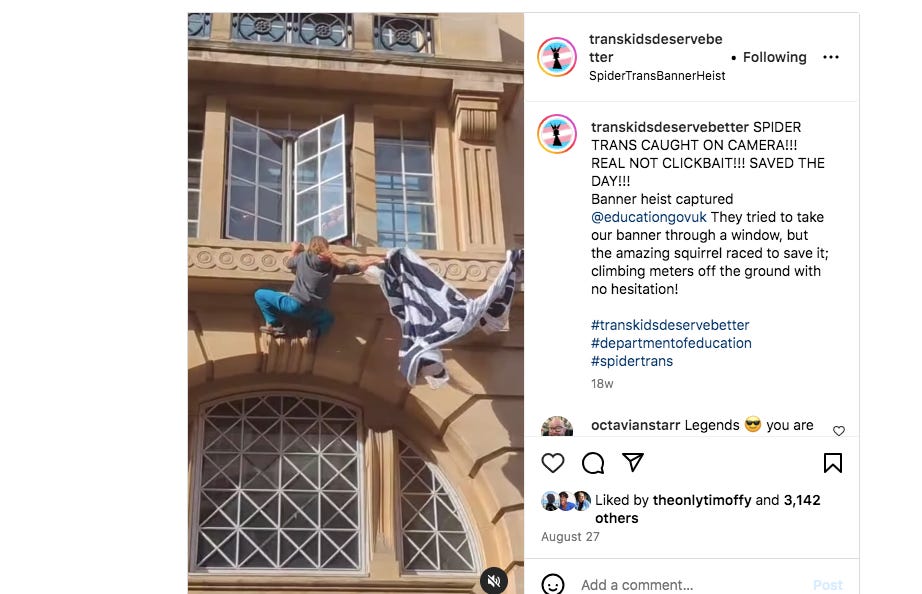

The windows of that NHS building may seem firmly shut, for now — but Trans Kids have learned to scale walls.

In the months since July, their actions have continued. Trans Kids Deserve Better have shown signs of dedication, persistence and creativity, finding new and disruptive ways to place their actual trans bodies and life experiences in the paths of powerful policy-makers who would rather ignore them.

Whether you are Biden or a Streeting, it becomes all too easy with age and power to insulate yourself from the harm you’re causing. Please, as I age into queer elderhood, let me not become an embarrassment like Stephen Fry (newly knighted?!, vomit), who in an interview with a libertarian podcast offered an object lesson in self-satisfied drawbridge-raising.

Fry admitted that he had once supported the agenda of LGBT charity Stonewall, back when it was fighting for causes that affected him directly, like marriage equality or raising the age of consent. Since it had turned its attention to a ‘nonsensical’ trans rights agenda, though, he feels it’s been ‘stuck in a terrible, terrible quagmire.’

In fact, Stonewall’s evolution indicates a organization that is hardly stuck, but open and flexible. It’s true we can’t prevent our joints from stiffening with age. I won’t climb a wall with the dexterity of a seventeen year-old, but I can stretch my empathy to see beyond narrow self-interest and find common cause with others.

There is a lesson embedded in the very name of ACT-UP, which stands for ‘AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power’: if we wait passively for power to be handed over, systems never change. If we organise in coalition, our collective powers are harnessed and unleashed, making those systems more difficult to operate.

Strength and liberation can come from sharing power, linking hands, gathering forces. If any generation holds too firmly to its own power and privilege, our community’s capacity for resistance will atrophy, and the fascists will win.

Freedom depends not on what’s been won before, but what we do next.